Perceived Value and Customer Adoption of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

3. Research Method

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.2. Goodness of Fit Tests

4.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

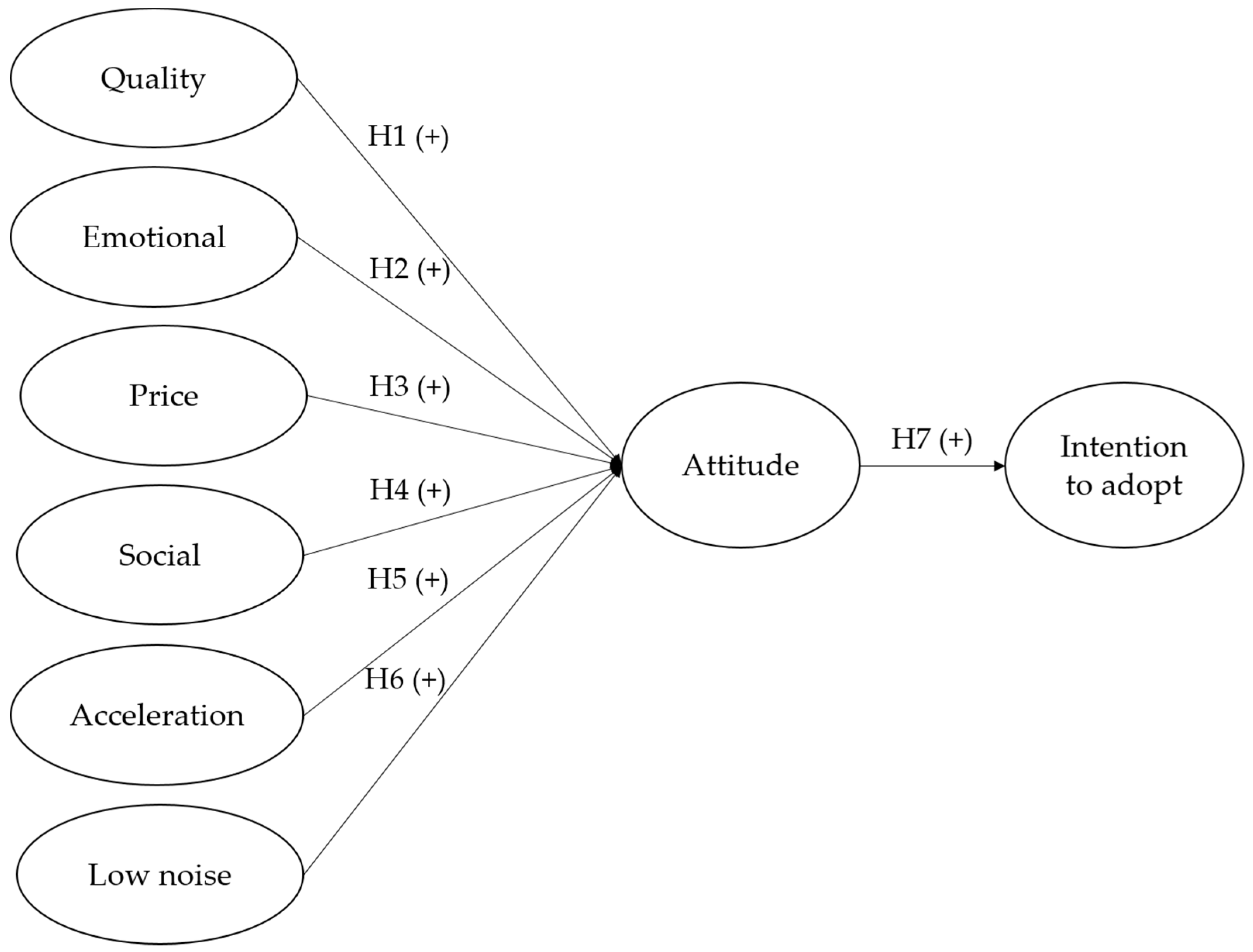

- The majority of research carried out to date on consumer attitudes towards EM vehicles has focused on people’s attitudes towards the environment and barriers to the purchase of EM vehicles [6]. All in all, the findings of this study suggest that the adoption of EM vehicles depends on a wide array of factors (e.g., government incentives and policies, vehicle characteristics, infrastructure availability, price, social and personal issues, environmental concerns) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,54]. Building on studies related to the adoption of new technologies [33,34,35,36,37], this study is one of a few to investigate consumers’ perceived value and its effect on their attitude towards EM vehicles. As opposed to earlier research on this topic, where different measures of consumer perceived value have prevailed as antecedents to purchase intention of EM vehicles [18], this study instead evaluated the influence of four PERVAL dimensions on consumer attitudes within a theoretical framework based on the theory of perceived value [23] and incorporating the theory of reasoned action [24] to take into account the effect of perceived outcome on customers’ intentions to purchase EM vehicles. Among the wide range of perceived value dimensions [29], this study showed that a four-dimension conceptual approach (i.e., quality, emotional value, price and social value) [30,31,32] is suitable to capture the meaning of the concept. Therefore, this study adds to earlier research on the impact of perceived value on consumers’ intention to use transport means [18,19,27,28].

- The model posited in this study merged PERVAL with two consumer attitude antecedents identified as two of the dimensions of EM vehicle performance most valued by consumers [38,39,40,41,42,43]. To date, no other study has evaluated the attitude of consumers towards EM vehicles on the basis of customers’ perceived value and vehicle performance. The outcome of this analysis is a model that is easy to use and one that explains to a large extent the diversity of consumer attitudes and their intentions to purchase EM vehicles.

- This study identified emotional value and value for money as key motivating factors for consumers to purchase EM vehicles. These results are in line with earlier studies carried out in a different cultural context (e.g., China and Malaysia [18,55]) and appear to hold true for the Spanish market too. The findings of this analysis indicate that potential buyers of EM vehicles are influenced primarily by emotions and the experience of driving an EM vehicle, followed by the product’s value for money. Thus, this study makes a significant contribution to current knowledge on EM vehicle adoption, as it adds to the findings of earlier research and provides an improved understanding of their validity in a different cultural context.

- This research showed that rapid vehicle acceleration and low engine noise are two key characteristics, which have a positive influence on consumer attitude. These results expand the findings of earlier studies [42,43,49] and contribute significantly to the literature, given that no other research study to date has evaluated the direct effect of vehicle performance on consumer attitudes towards EM vehicles. Therefore, the findings of this study improve our understanding of the attitude antecedents and, accordingly, the determinants of consumers’ behaviour [24] in this respect.

- Contrary to one of the hypotheses tested as part of this analysis, product quality did not have a significant influence on consumer attitudes. Although earlier studies have shown that perceptions of quality have an influence on purchase decisions of internal combustion engine vehicles [56] and hybrid vehicles [57], this particular research finding may be explained by the fact that the study was carried out with potential consumers who had yet to test drive the vehicles and, as such, had limited information on this particular factor. In fact, a number of earlier studies have suggested that test driving of EM vehicles tends to have a significant impact on consumers’ perceptions and attitudes towards these vehicles [58]. In addition to this, given the low market share of EM vehicles at present, the effects of peer-to-peer communication as regards information sharing among customers are lower than for more established alternatives in the market, i.e., internal combustion engine vehicles. This has, in effect, an adverse impact on the possibility of quality perceptions influencing product purchase intentions in the particular case of EM vehicles in Spain [57]. Therefore, this study makes a distinct contribution to the literature by stressing the importance of promoting the product’s quality actively, particularly for innovative solutions such as EM vehicles.

- The social dimension did not have a significant level of influence on consumer attitudes towards EM vehicles. This is in spite of the fact that a number of studies have shown that social factors are key in influencing people’s attitudes towards new technologies [59] including EM vehicles [14]; this study showed that social value does not have any effect. This may be due in part to the low market share currently enjoyed by EM vehicles in Spain as well as the general lack of information about this consumer segment, which reduces any social pressures that consumers may have experienced with regards to purchasing EM vehicles. Consequently, in line with earlier research [31,60], this study showed that for the embryonic stages of the market development of innovative technologies such as EM vehicles, social factors are not crucial as regards the adoption of these technologies by customers.

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Future Research and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- White, L.V.; Sintov, N.D. You are what you drive: Environmentalist and social innovator symbolism drives electric vehicle adoption intentions. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 99, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Long, R.; Chen, H. Consumers’ evaluation of national new energy vehicle policy in China: An analysis based on a four paradigm model. Energy Policy 2016, 99, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, J.; Rao, R.; Liang, Y. Policy incentives for the adoption of electric vehicles across countries. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8056–8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Long, R.; Li, W.; Rehman, S.U. Innovative application of the public–private partnership model to the electric vehicle charging infrastructure in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauers, A.; Sarasini, S.; Karlstrom, M. Why Electromobility and What Is It? In Systems Perspectives on Electromobility; Sandén, B., Wallgren, P., Eds.; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2013; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bodin, J. Advances in consumer electric vehicle adoption research: A review and research agenda. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 34, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shafiei, E.; Thorkelsson, H.; Ásgeirsson, E.I.; Davidsdottir, B.; Raberto, M.; Stefansson, H. An agent-based modeling approach to predict the evolution of market share of electric vehicles: A case study from Iceland. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2012, 79, 1638–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, R.R.; Kurani, K.S.; Turrentine, T.S. Symbolism in California’s early market for hybrid electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2007, 12, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.E. Do greens drive Hummers or hybrids? Environmental ideology as a determinant of consumer choice. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 54, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.S.; Muehlegger, E. Giving green to get green? Incentives and consumer adoption of hybrid vehicle technology. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noppers, E.H.; Keizer, K.; Bolderdijk, J.W.; Steg, L. The adoption of sustainable innovations: Driven by symbolic and environmental motives. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 25, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, I.; De Pelsmacker, P. An extended decomposed theory of planned behaviour to predict the usage intention of the electric car: A multi-group comparison. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6212–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, C. Does driving range of electric vehicles influence electric vehicle adoption? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, C.; Pucci, T.; Silvestri, C.; Aquilani, B. Does Value Co-Creation Really Matter? An Investigation of Italian Millennials Intention to Buy Electric Cars. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bengtsson, M. Consumer motivations for sustainable consumption: The interaction of gain, normative and hedonic motivations on electric vehicle adoption. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Molin, E.; Timmermans, H.; van Wee, B. Consumer preferences for business models in electric vehicle adoption. Transp. Policy 2019, 73, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietmann, N.; Lieven, T. A comparison of policy measures promoting electric vehicles in 20 countries. In The Governance of Smart Transportation Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. Purchase Intention for Electric Vehicles in China from a Customer-Value Perspective. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Douglas, M.A.; Hazen, B.T.; Dresner, M. Be green and clearly be seen: How consumer values and attitudes affect adoption of bicycle sharing. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 58, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expansión. España: Matriculaciones de Vehículos Nuevos. 2019. Available online: https://datosmacro.expansion.com/negocios/matriculaciones-vehiculos/espana (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica. Plan Nacional Integrado de Energía y Clima (PNIEC) 2021–2030. 2019. Available online: https://www.idae.es/informacion-y-publicaciones/plan-nacional-integrado-de-energia-y-clima-pniec-2021-2030 (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- ANFAC. Las Matriculaciones de Vehículos Electrificados, Híbridos y de Gas Crecen un 37% en Abril; Asociación Española de Fabricantes de Automóviles de Camiones: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: http://www.anfac.com/noticias.action (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, R.; Sevastyanova, K. Going hybrid: An analysis of consumer purchase motivations. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 2217–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.T.; Chen, C.F. Behavioral intentions of public transit passengers—The roles of service quality, perceived value, satisfaction and involvement. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F. Investigating structural relationships between service quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for air passengers: Evidence from Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, R.; Iniesta-Bonillo, M.Á. The concept of perceived value: A systematic review of the research. Mark. Theory 2007, 7, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. User acceptance of wireless short messaging services: Deconstructing perceived value. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, G.; Shiu, E.; Hassan, L.M. Replicating, validating, and reducing the length of the consumer perceived value scale. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.E.; Sherrell, D.L.; Babakus, E.; Horky, A.B. Understanding the differences of public and private self-service technology. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, E. Beyond coolness: Predicting the technology adoption of interactive wearable devices. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinillo, S.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Pérez-García, F. The effects of human-game interaction, network externalities, and motivations on players’ use of mobile casual games. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 1766–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Y. A cross-country study of consumer innovativeness and technological service innovation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Jolly, L.D. The effects of consumer perceived value and subjective norm on mobile data service adoption between American and Korean consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Park, H. Impact of experience on government policy toward acceptance of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in Korea. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3465–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, Z.Y.; Sun, Q.; Ma, J.J.; Xie, B.C. What are the barriers to widespread adoption of battery electric vehicles? A survey of public perception in Tianjin, China. Transp. Policy 2017, 56, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D.; Li, J. The intention to adopt electric vehicles: Driven by functional and non-functional values. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skippon, S.M. How consumer drivers construe vehicle performance: Implications for electric vehicles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014, 23, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skippon, S.; Garwood, M. Responses to battery electric vehicles: UK consumer attitudes and attributions of symbolic meaning following direct experience to reduce psychological distance. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalfuß, F.; Mühl, K.; Krems, J.F. Direct experience with battery electric vehicles (BEVs) matters when evaluating vehicle attributes, attitude and purchase intention. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 46, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Higgins, C.; Ferguson, M.; Kanaroglou, P. Identifying and characterizing potential electric vehicle adopters in Canada: A two-stage modelling approach. Transp. Policy 2016, 52, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petschnig, M.; Heidenreich, S.; Spieth, P. Innovative alternatives take action–Investigating determinants of alternative fuel vehicle adoption. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2014, 61, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D. Exploring urban resident’s vehicular PM2. 5 reduction behavior intention: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yan, R. Research on consumers’ use willingness and opinions of electric vehicle sharing: An empirical study in shanghai. Sustainability 2016, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.; Shang, J. Is subsidized electric vehicles adoption sustainable: Consumers’ perceptions and motivation toward incentive policies, environmental benefits, and risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, I.; De Pelsmacker, P. Emotions as determinants of electric car usage intention. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 195–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Moons, I. Personal Values, Green Self-identity and Electric Car Adoption. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, I.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, W. Factors influencing the behavioural intention towards full electric vehicles: An empirical study in Macau. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12564–12585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.N.; Bekhet, H.A. Modelling electric vehicle usage intentions: An empirical study in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraj, S.; Matta, K.F.; Conlon, E. Product and service quality: The antecedents of customer loyalty in the automotive industry. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2001, 10, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heutel, G.; Muehlegger, E. Consumer learning and hybrid vehicle adoption. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2015, 62, 125–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.F.; Cherchi, E.; Mabit, S.L. On the stability of preferences and attitudes before and after experiencing an electric vehicle. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2013, 25, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalinic, Z.; Marinkovic, V.; Molinillo, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. A multi-analytical approach to peer-to-peer mobile payment acceptance prediction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Molinillo, S.; Ruiz-Montañez, M. To use or not to use, that is the question: Analysis of the determining factors for using NFC mobile payment systems in public transportation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 139, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, C.; Pratesi, C.A.; D’agostino, A. A benefit segmentation of the Italian market for full electric vehicles. J. Mark. Anal. 2014, 2, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Quality | EM offers reliable levels of quality. | [32] |

| EM vehicles are well made. | ||

| Emotional value | EM is something I would enjoy. | |

| EM would make me feel good. | ||

| Price | EM offers value for money. | |

| EM is a good product for the price. | ||

| Social value | EM would improve the way I am perceived by others. | |

| EM would make a good impression on other people. | ||

| Acceleration | I would perceive the fast acceleration of EM as pleasant. | [43] |

| The immediate acceleration increases the driving comfort of EM. | ||

| I would like the fast acceleration of the EM. | ||

| Low engine noise emission | The lack of engine noise of EM increases the pleasure of driving. | |

| I would like the low soundscape of EM. | ||

| I would not need to change my driving style due to the lack of engine noise of the EM. | ||

| I believe that the lack of noise from the EM is not dangerous for road traffic. | ||

| The lack of engine noise would not make driving more difficult. | ||

| Attitude | In the long term, I think buying an EM vehicle is more cost effective than owning a conventional (internal combustion engine) vehicle. | [44] |

| Buying an EM vehicle will help to mitigate the effects of climate change. | ||

| I think buying an EM vehicle is a good decision. | ||

| Intention to adopt | Next time I buy a car, I will consider buying an EM vehicle. | [49,50] |

| I expect to drive an EM car in the near future. | ||

| I intend on driving an EM vehicle in the near future. |

| Variable | Description | Frequency | % in Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 206 | 51.0 |

| Male | 198 | 49.0 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 55 | 13.6 |

| 26–35 | 111 | 27.5 | |

| 36–45 | 77 | 19.1 | |

| 46–55 | 74 | 18.3 | |

| 56–65 | 56 | 13.9 | |

| More than 65 | 31 | 7.7 | |

| Education | Basic schooling or less | 21 | 5.2 |

| Vocational training | 114 | 28.2 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 178 | 44.1 | |

| Postgraduate degrees | 91 | 22.5 | |

| Employment status | Unemployed | 37 | 9.2 |

| Student | 43 | 10.6 | |

| Employed | 237 | 58.7 | |

| Self-employed | 39 | 9.7 | |

| Retired | 48 | 11.9 | |

| Monthly income (Euros) | No income | 37 | 9.2 |

| Less than €1100 | 73 | 18.1 | |

| From €1100 to €1800 | 135 | 33.4 | |

| From €1800 to €2700 | 95 | 23.5 | |

| More than €2700 | 40 | 9.9 | |

| Do not know/No answer | 24 | 5.9 | |

| Experience as a driver (years) | 0–1 | 27 | 6.7 |

| 1–3 | 34 | 8.4 | |

| 3–5 | 32 | 7.9 | |

| 5–8 | 207 | 51.2 | |

| More than 8 | 104 | 25.7 | |

| Annual distance driven (km) | Up to 2500 | 78 | 19.3 |

| Up to 7500 | 77 | 19.1 | |

| Up to 12,500 | 75 | 18.6 | |

| Up to 15,000 | 57 | 14.1 | |

| Up to 20,000 | 64 | 15.8 | |

| Up to 32,500 | 31 | 7.7 | |

| More than 32,000 | 21 | 5.2 |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | Q1 | 0.80 | N/A | 0.836 | 0.719 |

| Q2 | 0.89 | ||||

| Emotional value | E1 | 0.91 | N/A | 0.910 | 0.834 |

| E2 | 0.92 | ||||

| Price | P1 | 0.90 | N/A | 0.916 | 0.845 |

| P2 | 0.93 | ||||

| Social value | S1 | 0.86 | N/A | 0.878 | 0.782 |

| S2 | 0.90 | ||||

| Acceleration | Acc1 | 0.79 | 0.860 | 0.863 | 0.679 |

| Acc2 | 0.88 | ||||

| Acc3 | 0.80 | ||||

| Low noise | LN1 | 0.71 | 0.873 | 0.876 | 0.586 |

| LN2 | 0.75 | ||||

| LN3 | 0.77 | ||||

| LN4 | 0.70 | ||||

| LN5 | 0.88 | ||||

| Attitude | ATT1 | 0.82 | 0.868 | 0.863 | 0.679 |

| ATT2 | 0.76 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.88 | ||||

| Intention to adopt | IA1 | 0.76 | 0.944 | 0.910 | 0.772 |

| IA2 | 0.86 | ||||

| IA3 | 0.70 |

| Quality | Emotional | Price | Social | Acceleration | Low Noise | Attitude | Intention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | 0.848 | - | ||||||

| Emotional | 0.642 | 0.913 | - | |||||

| Price | 0.487 | 0.382 | 0.919 | - | ||||

| Social | 0.437 | 0.445 | 0.406 | 0.884 | - | |||

| Acceleration | 0.171 | 0.145 | 0.158 | 0.134 | 0.824 | - | ||

| Low noise | 0.008 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.766 | - | |

| Attitude | 0.352 | 0.451 | 0.597 | 0.504 | 0.326 | 0.279 | 0.824 | - |

| Intention | 0.357 | 0.514 | 0.638 | 0.512 | 0.330 | 0.263 | 0.253 | 0.879 |

| Fit Indices | CMIN | GFI | CFI | TLI | IFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended value 1 | 1–5 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.08 |

| Value of the model | 2.298 | 0.911 | 0.962 | 0.953 | 0.962 | 0.057 |

| Research Hypotheses | β | p-Value | Results | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality ⟶ Attitude | −0.020 | 0.822 | Not supported | - |

| Emotional ⟶ Attitude | 0.619 | 0.000 | Supported | - |

| Price⟶ Attitude | 0.181 | 0.000 | Supported | - |

| Social ⟶ Attitude | 0.046 | 0.383 | Not supported | - |

| Acceleration ⟶ Attitude | 0.121 | 0.004 | Supported | - |

| Low noise ⟶ Attitude | 0.071 | 0.049 | Supported | - |

| Attitude ⟶ Intention | 0.945 | 0.000 | Supported | - |

| Attitude | - | - | - | 0.757 |

| Intention | - | - | - | 0.652 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Higueras-Castillo, E.; Molinillo, S.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Perceived Value and Customer Adoption of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184956

Higueras-Castillo E, Molinillo S, Coca-Stefaniak JA, Liébana-Cabanillas F. Perceived Value and Customer Adoption of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Sustainability. 2019; 11(18):4956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184956

Chicago/Turabian StyleHigueras-Castillo, Elena, Sebastian Molinillo, J. Andres Coca-Stefaniak, and Francisco Liébana-Cabanillas. 2019. "Perceived Value and Customer Adoption of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles" Sustainability 11, no. 18: 4956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184956

APA StyleHigueras-Castillo, E., Molinillo, S., Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., & Liébana-Cabanillas, F. (2019). Perceived Value and Customer Adoption of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Sustainability, 11(18), 4956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184956